Smart Restorative Materials: Evaluation of Bioactive Composite Resins in Caries Prevention and Long-Term Restoration Success

Author: Vasilis Deskas

Abstract

Bioactive composite resins are a breakthrough in restorative dentistry, actively responding to the oral environment by releasing ions and adapting the pH levels at the site of application. These materials go beyond traditional cavity restoration: they help prevent secondary caries and support repair of enamel and dentin. In this paper, we review recent advances (2019–2025) in these “smart” materials—spanning glass ionomer cements, giomers, and nano-calcium phosphate composites—evaluated for mechanical properties, biological activity and biocompatibility, and clinical effectiveness in both children and adults. We compiled data from leading databases (PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scientific Reports, Frontiers in Oral Health, and BMC Oral Health) and integrated findings from manufacturer resources, including Pulpdent’s ACTIVA™ BioACTIVE, Shofu’s Beautifil® II, and Premier Dental’s Predicta™ Bulk Bioactive. Compared to traditional resins, these substances demonstrate improved mechanical properties and consistent ion release. Regardless, the absence of long-term research and varying protocols, especially in high-stress situations, limit their wider clinical implementation. We finish by recognizing new pathways and proposing the creation of cohesive clinical guidelines to more effectively incorporate bioactive composites into preventive restorative care.

Introduction

Dental composite resins are slowly becoming a mainstay for restoring carious lesions, yet their long-term performance has not come without its limitations. Over years of service, conventional composites may suffer from marginal deterioration, wear, discoloration, and polymerization shrinkage issues that can lead to microleakage and eventually secondary caries. In fact, a significant portion of restoration failures over time – roughly 20% – are related to recurrent caries at the margins. The majority of failures (nearly 70%) seem to be due to material fractures or mechanical wear. These statistics underscore a clinical need: restorative materials should not only restore tooth form and function but also actively help prevent future carious attacks and withstand functional stresses for extensive time periods.

The introduction of fluoride-releasing materials in restorative dentistry has been one of the ways to rectify this conundrum. Innovative products like resin-modified glass ionomers (RMGIs) and polyacid-modified composites (compomers) were implemented to offer some anticariogenic benefits by releasing fluoride into the hard tissues of the tooth. Fluoride release can strengthen the tooth’s structure by forming fluorapatite and make teeth more resistant to acidic demineralization. However, even with fluoride release, traditional materials remain relatively passive once placed – they don’t produce changes to the oral environment such as pH changes or reduce bacterial set-ins. The concept of bioactive composite resins has emerged to address this gap. The term “bioactive” in dentistry has been used somewhat broadly. In the context of this review, we consider a composite resin “bioactive” if it actively interacts with the surrounding oral tissues and fluids in a beneficial way. That is primarily accomplished through ion release that leads to anti-caries effects or regenerative outcomes (such as forming a mineralized layer at the tooth-material interface)

Bioactive composite resins are often dubbed “smart” materials by researchers because they interact with their surroundings in a more active manner than previously introduced materials. In theory, they can sense an acidic change (like the drop in pH that occurs when bacteria produce acids from sugars) and respond accordingly by releasing neutralizing ions or remineralizing agents. This behavior mimics a defensive mechanism – the material helps protect the tooth as an active participant, not just a passive bystander (Ástvaldsdóttir et al., 2015).

Bioactive composite resins typically incorporate components that release therapeutic ions such as fluoride (F⁻), calcium (Ca²⁺), phosphate (PO₄³) and even hydroxyl (OH⁻) ions which are supposed to minimize the damage that is caused in the oral cavity. These ions reverse pH changes, bringing the local environment to a more neutral or mildly alkaline level which blocks the acidic reactions of the oral bacteria. As a secondary utility, they also help with remineralization, helping with the repair of early lesions and prevention of future caries lesions. Such ion release might also directly inhibit cariogenic bacteria. In fact, laboratory studies have shown that the mix of ions from certain bioactive fillers can suppress Streptococcus mutans – the prime culprit in tooth decay – and even alter its gene expression in the presence of sugar. This is a remarkable finding: the restoration itself could exert a modest antibacterial effect and reduce plaque formation on its surface (Gordan et al., 2015).

Traditional glass ionomer cements were the pioneers of bioactivity in tooth-colored restoratives, thanks to their fluoride release and chemical bond to tooth structure. More modern materials build upon that with improved dental filling matrices and novel fillers to enhance chemical stability while not affecting bioactivity. Various chemical formulations have found themselves to the market from a wide variety of companies, some of them incorporate glass ionomer-based fillers, others include surface pre-reacted glass (S-PRG) fillers, and others add calcium phosphate nano-fillers or specialized alkaline resins, each one trying to handle the problem from a different angle but with the same principles, utilizing the preventive benefits of ionic releases with the strength and aesthetics of modern composite resins (Ástvaldsdóttir et al., 2015).

This review sets out to explore these smart restorative materials in detail. We will first survey the different types of bioactive composites available or in development (from glass ionomer hybrids to giomers and new bulk-fill formulations). Furthermore, we will examine evidence gathered regarding their mechanical properties, ion-releasing behavior, biocompatibility, and clinical effectiveness in a broad spectrum of the population. Ultimately, the goal is to understand if bioactive composite resins can usher in a new standard of restorative dentistry – one that not only fills cavities but also contributes to the ongoing health of the tooth. The article aims to also discuss future guidelines and also showcase the current limitations that these revolutionary materials suffer from (Tian et al., 2024).

Literature Review

Evolution of Bioactive Restoratives: The concept of bioactive restorative materials did not appear overnight – it evolved from earlier materials that showed the value of ion release. Glass Ionomer Cements (GICs) were among the first widely used materials to offer fluoride release and a chemical bond to tooth structure. GICs and their resin-modified versions adhere inherently to enamel and dentin and have a thermal expansion similar to tooth structure, plus high biocompatibility. These properties made them especially attractive for some specialized uses (usually in pediatric and geriatric dentistry). Although, as a matter of fact, traditional GICs have well-recorded drawbacks: they are brittle with low fracture toughness, show high wear and solubility, and cannot reliably endure the high occlusal stresses in large, multi-surface restorations for the same period of time as the more conventional options we have. As an example, the typical compressive strengths of an RMGI are on the order of 150–160 MPa, whereas hybrid composite resins range around 260–290 MPa. In other words, a classic glass ionomer cannot survive the same pressure the modern composite resins can handle, limiting its uses in posterior teeth for example, where biting strength is the greatest. Despite these mechanical limitations, the bioactive trait of GICs – continuous fluoride release and the ability to recharge fluoride from the oral environment when it is found plentifully– laid the groundwork for the next generation of smart materials (Banon et al., 2024).

Giomers and S-PRG Technology: An important milestone in the development of bioactive composites was the introduction of giomers. Giomers are essentially composite resins that incorporate surface pre-reacted glass ionomer (S-PRG) filler particles. Each S-PRG filler has a glass core that has been partially reacted with polyacid to form a glass-ionomer phase on its surface. This unique three-layer structure means the filler carries within it the chemistry of a glass ionomer, including fluoride and other ions, but is sealed within a resin matrix. The result is promising. As the giomer is placed in the mouth, these fillers can release multiple ions (fluoride, sodium, strontium, aluminum, borate, etc.) in a sustained manner for long periods of time, especially in response to acid fluctuations. The release of fluoride from S-PRG is acidity-dependent – more acid in the environment triggers more fluoride release, a “quasi-intelligent” behavior that directs protection when and where it’s needed most. Additionally, the strontium and borate ions from S-PRG contribute to buffering the pH (shifting it toward neutral or weakly alkaline). These ions also have interactions with tooth mineral: strontium can replace calcium in the apatite lattice of enamel and dentin, forming a more acid-resistant strontium-apatite, and fluoride helps form fluorapatite. Essentially, giomer restoratives strive to fortify the adjacent tooth structure over time – a little like a constant guardian releasing reinforcements. Research even shows that S-PRG fillers can inhibit plaque formation. Fewer S. mutans bacteria adhere to surfaces containing S-PRG, and a reduced biofilm accumulation has been observed compared to conventional materials. This likely results from the ions (like fluoride and borate) creating less favorable conditions for bacteria, as well as possibly directly interfering with bacterial adhesion mechanisms.

A prime example of a giomer-based material is Beautifil® II (Shofu), which has been on the market for some time. Its long-term performance has been encouraging. Gordan et al. reported that Beautifil (paired with a self-etching adhesive) demonstrated excellent clinical results over 8 years, with no restorations failing in that period and only minor incidences of marginal discoloration or adaptation changes. In a follow-up at 13 years, the majority of those restorations still maintained acceptable characteristics on most factors (margins, shape, aesthetics etc.) just as they did 5 years before. The authors attributed this success, at least in part, to the beneficial properties of the S-PRG filler – implying that the material’s bioactive ion-releasing feature might have contributed to its long-term stability and resistance to secondary caries. It’s worth noting that such long-term data for bioactive composites are rare, making the giomer results particularly significant. At the same time, even proponents acknowledged that broader long-term data on giomers and other bioactive resins have been lacking in literature. Thus, while giomers show that marrying glass-ionomer chemistry with resin composites is a viable path, the dental community has awaited more evidence on newer bioactive products (Tian et al., 2024, Ástvaldsdóttir et al., 2015).

Resin-Based Bioactive Composites (Glass Hybrid Composites): Building on the success of giomers, manufacturers have developed what might be described as hybrid composites with bioactive glass fillers or ion-releasing additives. One prominent example is ACTIVA™ BioACTIVE (Pulpdent). Introduced in the mid-2010s, Activa BioACTIVE contains a resin matrix but also water-compatible rubberized resin and reactive glass fillers that release calcium, phosphate, and fluoride. Notably, Activa is BPA-free and does not use Bis-GMA, aiming for a more biocompatible resin chemistry. The material is dual-cure (self-cure with light-cure option) and is formulated to be more moisture tolerant. The manufacturer claims that Activa creates a hydroxyapatite-like layer at the tooth interface by continuously releasing and recharging calcium and phosphate ions, essentially inducing remineralization where the restoration meets the tooth. It also purportedly offers the advantages of glass ionomer (adhesion, fluoride release, thermal compatibility) but in a stronger, more fracture-resistant matrix. In essence, Activa tries to combine the best of composites and GICs: strength and esthetics on one side, ion release, and chemical bonding on the other. Early laboratory tests showed that Activa can indeed release significant amounts of fluoride, calcium and phosphate, though typically not quite as much fluoride as a pure GIC. Still, the ion release profile is robust and sustainable, and it can neutralize acidity similarly to traditional glass ionomers. Its physical properties (flexural and compressive strength, wear resistance) are reported to be closer to composite resins than to brittle GICs.

Another product in this category is Predicta™ Bioactive Bulk (Premier/Parkell) – a dual-cure bulk-fill bioactive composite. This material is designed for filling large restorations in one increment up to the occlusal surface. Despite being bulk fill, it is bioactive in that it releasesCa²⁺, PO₄³⁻, and F⁻ ions to stimulate apatite formation in the surrounding tooth structure. The idea is to use it like a regular bulk composite (with quick placement and depth-of-cure advantages) while gaining anti-caries benefits over time. Predicta Bulk is nano-filled and optimized for high strength and low shrinkage, so it tries to ensure that clinicians don’t have to compromise on handling or durability to get bioactivity. In short, it reflects a trend where bioactive features are being built into mainstream composite formulations (such as bulk-fills and core build-up materials) rather than treating “bioactive” as a niche category (Ástvaldsdóttir et al., 2015).

Alkasites and Other Novel Composites: A distinct approach to bioactivity in restorative materials is seen in products like Cention® N (Ivoclar). Cention N is described as an “alkasite” – essentially a new class of filling material that is alkaline in nature. Supplied as a powder-liquid system and self-cured (with optional light activation), Cention N’s filler includes special alkaline glass particles. When exposed to the oral environment these particles release hydroxide (OH⁻) ions alongside calcium and fluoride. The release of OH⁻ can reduce the adverse effects of the many acidic fluctuations that the oral cavity can undertake during the course of a patient’s life. Cention N has been pitched as an acceptable amalgam alternative for bulk placements. It offers a more esthetic, tooth-colored option compared to amalgam while also actively countering acidity. Though it is fundamentally a composite resin, its handling and chemistry (powder/liquid mix and self-cure) make it somewhat akin to glass ionomer or alloy in usage. Early evidence suggests Cention N performs reasonably well in terms of wear and retention over short periods, and it indeed elevates the local pH under acidic conditions. By incorporating fluoride in its structure, it can contribute to remineralization of the hard tissues as well (Öz et al., 2023).

Beyond these specific products, research is ongoing into nano-calcium phosphate (NCP) composites and many other, still experimental, bioactive resins. The materials in question have nano-sized calcium phosphate salts (such as amorphous calcium phosphate) implemented into the structure of the resin. When the material is in situ, saliva or lactic acid causes the nano-CaP to release various ions, potentially re-depositing them as apatite in decalcified enamel on the adjacent teeth. The point is to find the balance between strength and bioactivity. Nonetheless, progress in nanotechnology and filler silanization has made it possible to include such remineralizing fillers without completely sacrificing mechanical performance. The literature from 2019 onward includes reports of experimental composites with dual-function fillers (e.g., silica plus CaP) that show rechargeable remineralization capability. While not yet commercial, these studies indicate that the next generation of bioactive composites may further improve the ion release longevity and remineralization rates, all while narrowing the gap in physical properties compared to conventional composites.

Biological Activity and Biocompatibility: A vital aspect of bioactive restoratives is how they interact with the tooth and the pulp-dentin complex biologically. Materials like Activa BioACTIVE and giomers have generally shown good biocompatibility in laboratory and animal tests, with no significant cytotoxicity reported from their eluents. The absence of monomers like Bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) in some of these materials (Activa, for instance) is a reassuring aspect for biocompatibility. On the other hand, one must consider that the soluble ions these materials release – while beneficial for teeth – should not irritate the pulp. Fortunately, the buffering action (raising pH) is actually pulp-friendly in the event of microleakage, since lower acidity is less irritating than pulp tissue. Clinically, a number of trials have specifically monitored postoperative sensitivity and have found no increase in sensitivity with bioactive composites versus conventional ones. In fact, in several short-term clinical evaluations, neither the bioactive material nor the control group exhibited any post-op sensitivity, suggesting that these materials are at least as biologically neutral to the pulp as standard composites. Some bioactive materials, like giomers, even claim to have a beneficial effect on the adjacent dentin. There is intriguing evidence that S-PRG fillers can induce a form of dentin remineralization – essentially helping to mineralize affected dentin and perhaps forming a harder, more caries-resistant dentin layer under a restoration. This is still being studied, but if validated, could lead to a more proactive look in restorative dentistry (Tian et al., 2024).

In summary, all these different types of resins share a common goal to aid in the prevention of caries and the preservation of tooth structure but also offer a physically sound material that achieves what conventional resins offer in terms of restoration. Literature suggests that each type has its own strengths and ideal applications, which we will further examine through the findings of recent studies.

Methodology

This review adopted a narrative literature survey. Of the 36 references, 16 addressed the mechanical properties of the materials, while the remainder examined their bioactive characteristics. Materials considered included bioactive resin composites, giomers, glass-ionomer derivatives, and newer alkasite materials, all used as direct resin restorations. Evidence comprised both clinical and laboratory studies evaluating performance in long-term restorations.

Database search: Sources consulted included PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scientific Reports, Frontiers in Oral Health, and BMC Oral Health. Search terms encompassed “bioactive composite resin,” “giomer,” “bioactive dental material,” “ion-releasing composite,” “remineralising restoration,” and specific product names such as “ACTIVA BioACTIVE,” “Beautifil II,” “Cention N,” and “Predicta Bioactive.”

Selection criteria: Eligible studies comprised in vitro investigations measuring mechanical properties (e.g., strength, wear), ion-release profiles, pH fluctuations, and biocompatibility, as well as in vivo or clinical investigations—particularly randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, and case series—reporting clinical outcomes (e.g., restoration longevity, incidence of secondary caries, postoperative sensitivity). Both adult and paediatric populations were of interest, given the frequent targeting of bioactive materials to high-caries-risk groups. Studies outside restorative dentistry (e.g., bioactive endodontic materials, implant coatings) were excluded. General review articles were noted to identify consensus statements and divergent viewpoints.

Manufacturer information: Manufacturer perspectives were also considered. Technical brochures and product profiles from companies associated with bioactive restorative products—such as Pulpdent (Activa BioACTIVE), Shofu (Beautifil series with S-PRG fillers), and Premier/Parkell (Predicta Bioactive)—were analyzed. These documents often report composition, handling characteristics, and internal test results not present in peer-reviewed literature. Such claims were treated with appropriate caution; nevertheless, they aided in clarifying recommended clinical protocols and the theoretical advantages proposed for each material.

Data extraction: Key variables were extracted from all sources. For laboratory studies, these included material type(s), ion-release amounts (e.g., fluoride in ppm, phosphate in µg/cm²), pH changes, and reported effects such as apatite formation on adjacent substrates or antibacterial activity. For clinical studies, extracted items included number of restorations, follow-up duration, evaluation criteria (e.g., FDI, USPHS), success rates, reasons for failure, and comparative outcomes between bioactive and control materials.

Throughout the process, attention was given to the quality of evidence. Many clinical studies were short-term (1–2 years) RCTs with modest sample sizes, constituting a limitation. Protocols were heterogeneous: some trials applied USPHS criteria, others FDI criteria; some focused exclusively on Class I restorations, others on Classes I and II; some enrolled only paediatric patients, others only adults. These differences were considered when interpreting results.

Given the narrative design, a single risk-of-bias instrument was not uniformly applied across all studies; however, individual RCTs were appraised for randomisation methods, blinding of outcome assessment, and completeness of follow-up as reported by the authors. Relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses were cross-referenced where available; notably, a recent meta-analysis (2022–2023) pooling RCT data on bioactive materials was considered when formulating conclusions.

The discussion synthesises the principal findings and aims to balance encouraging results with appropriate caution regarding current product limitations.

Findings and Analysis

Ion Release and pH Modulation: A defining feature of bioactive composite resins is their ability to release beneficial ions. Recent laboratory studies have reinforced this capability. In one study comparing RMGI hybrid composite, Alkasite, an RMGI (resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI)), and a conventional composite (as a baseline), all the bioactive materials steadily released phosphate ions into distilled water, except the standard composite (3M Z250). After 24 hours of immersion, Resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI) showed the highest phosphate release (5.84 ± 0.50 µg/cm²), with Alkasite (3.98 ± 0.16 µg/cm²), Activa behind it (3.66 ± 0.50 µg/cm²) and standard composite (3M Z250) released negligible amounts (0.07 ± 0.15 µg/cm²). However, interestingly, after a prolonged period (6 months of storage in water), the order shifted: Alkasite leaped ahead to release the most cumulative phosphate (8.44 ± 0.88 µg/cm²), followed closely by Activa (7.70 ± 0.73 µg/cm²), surpassing the glass ionomer (5.18 ± 0.54 µg/cm²) and standard composite (3M Z250) (0.10 ± 0.18 µg/cm²). This suggests that the newer materials can maintain ion release over time and even recharge or continue to release later points, whereas the initial burst from the glass ionomer might taper off. In all cases, the conventional composite resin (which has no such ion-leachable fillers) remained inert, as expected (Öz et al., 2023).

Accompanying the ion release, these materials demonstrated significant pH-buffering (alkalizing) effects. Upon an artificial acidic challenge (immersion of the restorative material specimens in lactic acid solution adjusted to pH 4.0, simulating the acidic conditions produced by cariogenic bacteria during a caries attack), Resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI), Alkasite, and Activa each were able to raise the pH of the environment within an hour, whereas the control composite could not. Resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI) had the greatest alkalizing ability (~4.46 strong alkalizing effect) (no surprise, given GICs are known to neutralize acids by dissolving their basic glass), but Alkasite (~4.39 moderate alkalizing effect) and Activa were not far behind (~4.28 mild alkalizing effect). All three raised the pH well above the acid challenge baseline. Essentially, no pH drop goes unanswered when these materials are around – a promising sign for their potential to protect against acid-induced demineralization. The net result of these properties led researchers to conclude that using bioactive restorative compounds is a promising method to ensure continuous ion availability for remineralization and to maintain a less acidic environment in the vicinity of the restoration. Over time, these effects could translate to re-hardened enamel at margins and suppression of bacteria that prefer acidic niches.

Furthermore, specific ion-release profiles have been linked to particular benefits. Fluoride release, common to all these materials, helps with remineralizing tooth minerals into fluorapatite, which is more acid-resistant. The presence of calcium and phosphate ions is equally crucial – one without the other would be insufficient to remineralize; together they can deposit as new apatite mineral in demineralized enamel. In Activa’s case, both Ca²⁺ and PO₄³⁻ are released in giomers, strontium plays a dual role by substituting into enamel and raising pH (since strontium ions tend to reduce acidity similarly to calcium). Specifically, after 6 months the released PO₄³⁻ in each material is: RMGI hybrid composite 1.45 ppm, Alkasite 1.59, resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI) 0.98 ppm and 3M Filtek Z250 (composite) 0.02 ppm. In addition, the released Ca²⁺ after 21 days for RMGI hybrid composite is 0,768ppm and for resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI) 0.525ppm. (Öz et al., 2023, Bhatia et al. 2022).

We also see borate ions from S-PRG giomers contributing a buffer capacity. The combined evidence from multiple studies confirms that bioactive restoratives act as ion reservoirs, with the potential to repair early caries lesions around the restoration. In practical terms, one might expect, for instance, that a margin which isn’t perfectly sealed or is subjected to plaque accumulation would be less likely to develop a serious secondary caries lesion if the restoration is actively leaching fluoride, calcium, and alkalizing ions into that interface. This is a compelling advantage over inert composites – at least on paper (or in vitro) (Tian et al., 2024).

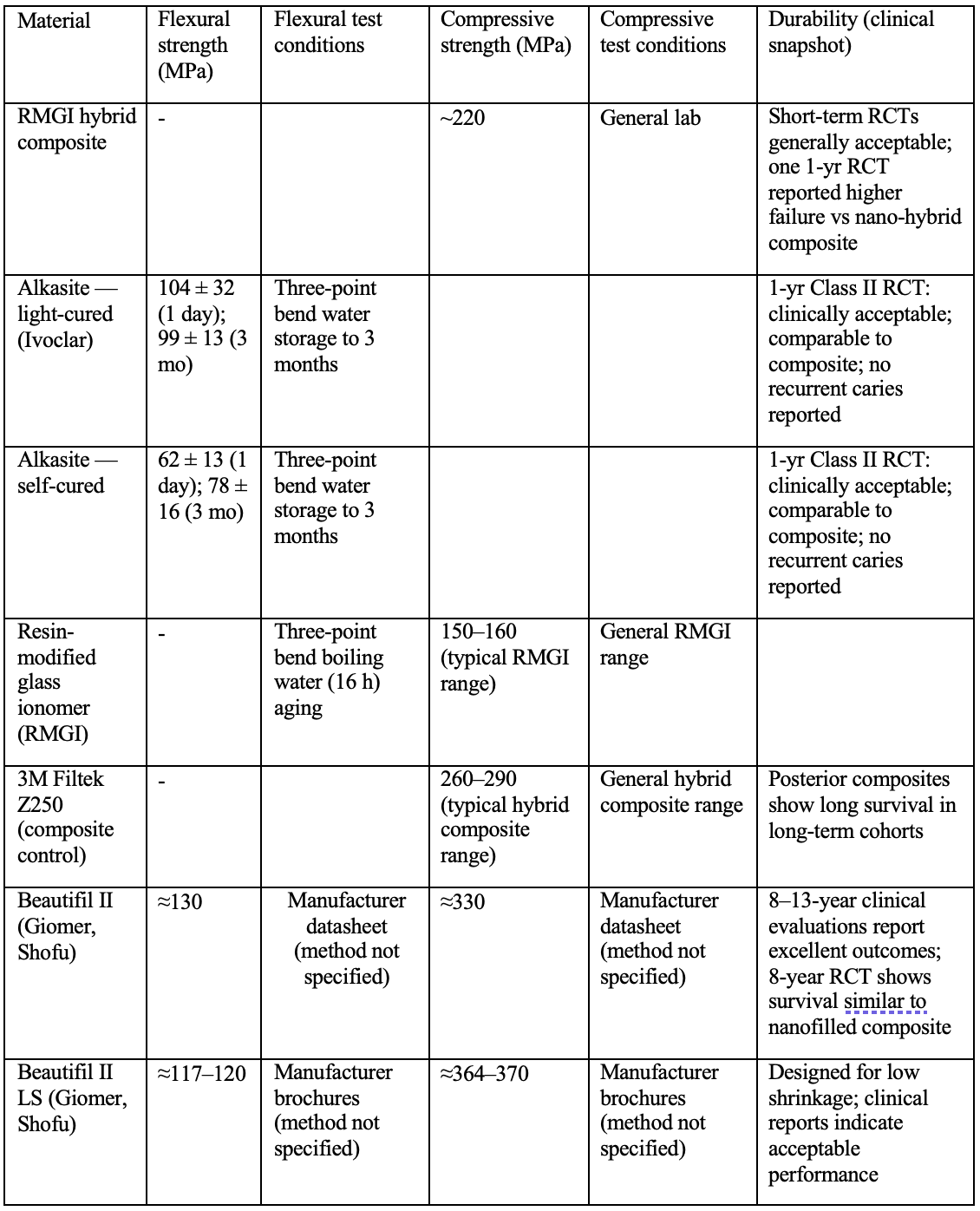

Mechanical Properties and Durability: The enthusiasm for ion release must be balanced with an equally important aspect: can these bioactive composites mechanically hold up as well as (or nearly as well as) the best conventional composites? The findings here are a bit of a mixed bag but generally positive for short to medium term. Manufacturers of bioactive materials have made significant improvements in the resin matrices and filler loading of these products to narrow the gap. For example, RMGI hybrid composite boasts flexural and compressive strength values in the same ballpark as hybrid composites (some reports cite compressive strength ~ 220 MPa, which, while somewhat lower than top-tier composites at ~250+ MPa, is higher than traditional RMGIs by a wide margin). Alkasite, designed as an amalgam replacement, has been shown to have high flexural strength (~over 100 MPa, which qualifies it for class II use per ISO standards) and good fracture toughness. One laboratory wear simulation study (2020) indicated that Alkasite’s wear resistance was comparable to a hybrid composite after cyclic loading, with no catastrophic fractures – an important finding if it’s to be used in large posterior restorations.

Clinical data gives us the proof for the durability of the composites in question. Several recent 1–2 year old RCTs have evaluated these materials head-to-head with conventional composites. In Class I (occlusal) cavities, which are placed in low-stress areas of the mouth compared to large Class IIs, bioactive materials have performed excellently. Sharma et al. (2023) made a trial in children with occlusal cavities, comparing the Cention N to a nanoparticle composite (Filtek Z350XT). At the one-year mark, all restorations in both groups were intact (100% retention) with predominantly perfect “Alpha” scores by USPHS criteria. The only minor differences noted were that in the Alkasite group a couple of restorations got a “Bravo” (slightly suboptimal) rating for anatomical form and surface roughness (around 10% of cases) whereas the nanoparticle composite group did not. These differences were not statistically significant, and importantly there were no secondary caries or post-op sensitivities in either group. Essentially, Alkasite was not found inferior to a modern material (for the span of a one-year trial).

For Class II (interproximal) restorations, which experience higher stress, the data is more limited but still encouraging in short term. One trial by Ozer et al. (2023) looked at Alkasite versus a composite (GC G-ænial Posterior) in Class II restorations over 1 year. They found a slightly lower retention rate for Cention (one or two of the 100 restorations lost, 87% retention vs 97.7% for composite). However, this difference did not translate into statistically significant differences in overall success, because the sample might have been too small for a few failures to show significance. For most evaluated criteria – marginal adaptation, discoloration, surface texture – there were no significant differences between Alkasite and composite. Neither material showed any secondary caries or post-op sensitivity at one year, and both were considered clinically acceptable with good survival rates (~93–98%). These short-term results indicate that the new alkasite and bioactive composites can hold their own structurally, at least within the first year or two, even in moderately sized posterior restorations.

The giomer materials (e.g., Beautifil) have longer-term data. Aside from Gordan’s 8-year and 13-year observational results mentioned earlier, a recent 8-year RCT by Tian et al. (2024) compared a giomer composite (Beautifil II) to a nanofilled composite (3M Filtek Supreme/“2350”) in a larger sample of Class I and II restorations. After eight years, the survival probability was essentially identical: ~87% for giomer vs ~88% for the conventional composite. The annual failure rates were 1.6% and 1.5% respectively – a negligible difference. The failures that did occur were due to typical reasons (a handful of fractures, a few secondary caries, some endo-required teeth), with no predominant failure mode that singled out one material as worse. In terms of qualitative criteria, both materials were mostly rated well for things like retention, marginal adaptation, etc. There were minor differences noted: the nanofill composite showed slightly less surface staining and perhaps marginally less incidence of secondary caries, whereas the giomer had slightly fewer instances of restoration fracture. These tendencies align with what one might expect: the giomer’s S-PRG filler may reduce caries (due to fluoride release) but the resin might be a tad less tough than the highly optimized nanoparticle composite (hence a hair more fractures, though still very few). Crucially, none of those differences reached statistical significance; they are just observations. So, after 8 years, the giomer matched the well-established composite in overall clinical performance. This is a strong testament that including bioactive fillers (at least S-PRG) does not inherently compromise long-term durability if the material is well formulated.

In conclusion the previous data are summarized in the following table:

Prevention of Secondary Caries: Ultimately, the raison d’être of these materials is preventing secondary decay at the margins. Do they actually achieve that in practice? At one or two years, frankly, it’s hard to see a big difference – secondary caries typically takes longer to manifest. A meta-analysis published in 2022 (with data up to early 2021) attempted to see if bioactive materials (giomers, Activa, Cention, etc.) had different rates of secondary caries compared to inert composites. The pooled analysis found no statistically significant difference in risk of secondary caries between bioactive and control groups in the short term. This is not too surprising given that most included studies were under 2 years. Similarly, retention loss rates were statistically similar between the groups in that meta-analysis. In essence, within the first couple of years, a well-placed composite – bioactive or not – usually performs well; there isn’t enough time for many carious lesions to form if the patient maintains reasonable oral hygiene.

However, individual studies have reported subtle differences suggestive of anti-caries effects. For instance, Deepika et al. (2022) compared RMGI hybrid composite versus a fluoride-releasing flowable composite (Beautifil Flow Plus, a giomer) in children over 1 year. By 12 months, they noted no caries in either group (again, short span) but did find that Activa had superior marginal integrity – fewer instances of slight marginal breakdown – which they attributed to Activa’s “sealing ability”. A better marginal seal could indirectly reduce microleakage and thus caries risk. They also found Activa restorations kept their shape (anatomical form) and retention slightly better than the composite at one year. All restorations had no postoperative sensitivity. While these differences were small, the authors implied that the Activa (a bioactive RMGI/composite) might inhibit marginal deterioration, possibly due to its reactive nature and fluoride release. Another RCT by Banon et al. (2024) in a pediatric population (high caries risk children) found that after 2 years, Activa and a compomer (Dyract) had comparable high success (~93–95%). Interestingly, Activa showed significantly better color match over time (perhaps due to less staining) but conversely had slightly worse marginal discoloration than the compomer. Both materials had similar very low incidence of radiographic caries around them. These mixed outcomes highlight that bioactive materials are at least holding their own and sometimes showing a slight edge in specific parameters, but not a dramatic reduction in actual caries occurrence within the short review window.

The one study that stands out as a cautionary tale is by van Dijken, Pallesen, and Benetti (2019). They carried out a randomized controlled trial using RMGI hybrid composite Restorative in posterior Class I and Class II cavities, placing a total of 158 restorations (in a split-mouth design) and evaluating their performance over a 1year follow-up. The Activa group experienced a considerably higher failure rate. By one year, Activa had an annual failure rate of 24.1% compared to only 2.5% for the composite. A large number of Activa restorations failed within the first 6 months and by 1 year (versus only 2 failures in the composite group). Most of the failures in Activa were due to lost restorations (falling out), some due to postoperative hypersensitivity leading to endodontic intervention, and a few due to secondary caries. These are serious failure modes, indicating possibly poor bonding, insufficient strength, or handling issues with Activa in that study. The contrast was stark: 12 Activa failures vs 1 composite failure at 12 months if we read the data correctly. This single trial’s outcome is much worse than any other reports on Activa, so one wonders about the specifics – were there issues with the bonding protocol, patient selection (high occlusal stress perhaps), or something inherently problematic with that batch of material? The authors postulated that Activa might not yet be a suitable substitute for well-established composites in large, stress-bearing restorations, given the results that have been witnessed. It’s a clear reminder that new materials with promising outcomes can sometimes falter in real-world conditions, and with the lack of long-term studies it’s hard to know if van Dijken’s results are the exceptions or indicative of a broader concern. Notably, other trials (e.g., Bhadra et al. 2019) did not come to such catastrophic results for Activa; Bhadra reported no significant differences in 1-year outcomes between Activa and a nanohybrid composite in class II restorations. So, the evidence is very conflicting, leading us to believe that more evidence needs to come out and raise the need for consistency and technique sensitivity on these materials.

Clinical Performance in High-Caries Risk vs Low-Risk Groups: One hypothetical advantage of bioactive restorations is that they would provide patients with high caries risk (e.g., children with poor oral hygiene, xerostomic patients, etc.) with a more effective way to help their predicament, where the extra fluoride and pH buffering would be most needed in such cases. Some of the available data comes from pediatric dentistry. As mentioned, in children with multiple caries, Activa performed comparably to compomer and composite, but whether it prevented new lesions better is unclear over short spans. The Banon 2024 study actually measured both clinical and radiographic success and found both materials worked well in kids with high caries experience. It’s encouraging that bioactive materials are at least not overwhelmed in high-risk mouths, but longer follow-up would be required to see if, say, fewer recurrent caries pop up around Activa or giomer versus others in the long haul (Tian et al., 2024).

In adult populations (generally lower caries activity), the benefit may be subtle. The 8-year giomer vs composite study in adults didn’t show less caries for giomer – both had a couple of cases of secondary decay but not many. This might imply that in adults with decent oral hygiene, a good adhesive seal is more crucial than ion release; caries simply might not occur often enough to differentiate materials. On the flip side, in situations like cervical lesions or root caries, a bioactive material might have clearer advantages (e.g., releasing fluoride to protect adjacent root surface). While our review focus is on general class I/II restorations, it’s worth noting that a few studies on cervical non-carious lesions have shown that materials like giomers and compomers can reduce or prevent secondary caries or demineralization around the restoration margins compared to purely resin-based composites, thanks to fluoride release. This aligns with the notion that the preventive payoff of bioactive resins likely increases as the baseline caries challenge increases.

Other Findings: We should touch on any aesthetic and handling aspects because they factor in clinical success too. A few studies commented on color match and aesthetics over time. For instance, Activa vs compomer: Activa had better color stability (less change) over 2 years, but also some more marginal staining. Giomers are generally praised for good esthetics (Giomer composite looks like a composite and polishes well), and their long-term studies show acceptable surface appearance even at 8-13 years (some slight surface roughness or staining is possible, but nothing drastic). None of the bioactive materials reviewed were described as having worse aesthetic outcomes than composites in any study; if anything, differences are minor, or they perform slightly better in certain categories like color match (possibly due to their hydrophilic matrices absorbing less stain? This is speculative). Handling-wise, clinicians have noted that Activa, being a bit more flowable and self-cure, can be sticky or stringy, and one must use it according to manufacturer’s instructions (including a bonding agent, as recommended, though Activa is sometimes advertised as “self-adhesive,” using it without bonding can risk retention issues – which might explain van Dijken’s losses). Alkasite requires mixing but is then packable; it's quite user-friendly if one is used to amalgam or GIC placement techniques.

Summarizing: Bioactive composite resins have the prospect of delivering on their promise of a ‘smarter’’ material. They show at least comparable short-term performance in terms of retention and wear, with some studies even indicating small advantages in things like marginal integrity or reduced minor failures. With that being said, the data also highlight variability – not all materials perform equally on the same aspects (giomers have a strong long-term track record, whereas some Activa results have been mixed), and not all studies show significant differences in caries prevention within the same time frames. Practically speaking, the current generation of bioactive resins can be seen as mostly comparable conventional composites in the short term, with the potential for additional protective effects that may manifest over longer periods of time. Whether those protective effects translate to significantly extended restoration longevity or lower recurrent caries rates is something that only longer and more extensive studies will be able to say

Discussion

The advent of bioactive composite resins represents an exciting convergence of restorative dentistry and preventive dentistry. After reviewing the recent literature and results, we can say that these materials indeed show great promise – yet their current real-world impact appears to be evolving rather than revolutionary (at least so far). Several key themes emerged in the discussion of their significance, advantages, and limitations:

1. Bioactivity is Real – But How Much Does It Help Clinically? There is no doubt that materials like giomers, RMGI hybrid composite, and Alkasite do what they claim chemically: they release fluoride and other ions, buffer acidity, and can aid in remineralization. This is a remarkable improvement over inert composites which, once cured, only degrade or wear but offer no therapeutic benefits. In vitro findings of ion release correlating with remineralization and antibacterial effects provide a mechanistic rationale that these materials could reduce secondary caries in patients. However, translating that to clinical reality has been challenging to verify. As our findings showed, within one or two years of placement, most restorations – bioactive or not – do fine, and differences in outcomes like secondary caries are minimal. It’s akin to giving two groups of generally healthy people vitamins vs no vitamins for a short period; major health differences might not materialize immediately. The preventive benefit of bioactive materials likely accrues over a longer horizon or becomes apparent in those with elevated disease challenge. So, while we are enthused by the biological activity of these materials, we must also be careful not to overstate their clinical effect until longer-term data emerges. The concept of a “smart” restoration that guards the tooth is very attractive, and logically it should contribute to longer restoration life by preventing recurrent decay – but proof of that in long-term trials is still pending. The discussion in the field is now centered on, “Yes, they release fluoride and raise pH, but will that restoration last 15 years instead of 10 because of it? Will patients actually experience fewer replacement drills?” Those questions remain open.

2. Mechanical Performance vs. Bioactivity – Achieving Balance: A critical discussion point is whether incorporating bioactivity compromises any of the physical properties. Traditional glass ionomers taught us that a trade-off existed: more fluoride, less strength. The newer materials have gone a long way toward mitigating that trade-off. As seen, giomers can last 8+ years like normal composites, and short-term RCTs report no significant differences in fractures or wear between bioactives and conventional composites. This is promising and gives room for theories that suggest that manufacturers have indeed produced products that maintain their structural integrity. It should be noted that not all bioactive materials are created equal, as it goes for most materials in the practice. The outlier case of Activa’s higher failure rate in one study is a stark reminder that some formulations might be more technique-sensitive or less tolerant of certain conditions. It raises an interesting discussion: why did Activa fare poorly there? One possibility is isolation and bonding – Activa, being more hydrophilic, might require very good moisture control until it sets, or it may not adhere as strongly to tooth structure if not light-cured promptly or if no adhesive is used. It also might be slightly less wear-resistant in big stress areas. Therefore, a prudent approach for clinicians is to follow manufacturer instructions to the letter for these new materials and perhaps start by using them in scenarios where they are likely to succeed (for instance, Activa in smaller restorations or sandwich techniques, Alkasite in single-surface or as a base, giomer pretty much anywhere given its track record). Over time, as confidence builds, their use can expand. The discussion among experts often highlights that bioactive composites should complement, not necessarily replace, traditional composites across the board at this stage. For example, one might use a bioactive material in a high-risk patient or in a deep cavity where a little pulp therapy effect is desired, but stick to a tried-and-true composite in a very large Class II on a heavy bruxer – at least until more evidence suggests otherwise (Öz et al., 2023).

3. Variability and Standardization Issues: One challenge we faced during the creation of this review is the lack of standardized evaluation criteria and long-term clinical data. Conflicting studies utilizing completely different criteria made it difficult to directly compare outcomes of the few multi-year trials that have been recorded. We all could benefit from more rigid criteria in order to really evaluate if these materials are worth pursuing. For example, if a multicenter trial were to take place where several bioactive materials and a conventional composite are all tested under roughly the same conditions for a period of 5 years, it would greatly clarify how they measure up to more studied composites. Furthermore, the term “bioactive” is mostly found in marketing campaigns from various manufacturers, which can cause confusion practitioners. Some manufacturers even label a material bioactive simply because it releases fluoride, even if it’s in minimal quantities. There is a great deal of discussion in the materials science community about setting clear standards for what qualifies as “bioactive”. Establishing specific benchmarks would prevent overuse of buzzwords and ensure that when a dentist sees “bioactive” on the label, it truly means what the clinician is expecting to get.

4. Clinical Guidelines and Integration into Practice: Given the current state of these materials, how should a practitioner approach these materials in everyday practice? This is where our review’s conclusion aligns with what many authors have called for: the development of cohesive clinical guidelines. These guidelines would ideally be based on consensus of available evidence and expert opinion, and would help answer questions like: In which situations should I prefer a bioactive composite? How should I handle it differently? Should it be layered or used in bulk? Do I need a bonding agent or a liner with it? How do I finish it to preserve its surface (since a highly polished surface might release less fluoride vs a slightly rougher one that can “soak” up fluoride recharge)? Currently, without official guidelines, dentists are either adopting these materials based on personal preference or holding off due to uncertainty. A few trends can inform interim best practices. For example, in pediatric dentistry, where patient cooperation is limited and caries risk is high, using a bioactive material like Activa or a giomer for a faster single-step restoration that also leaches fluoride could be beneficial. In fact, some clinicians report using RMGI hybrid composite for interim therapeutic restorations or as a definitive restoration in primary teeth, finding that it handles like a thick flowable and saves time (with the bonus of fluoride release). In geriatric or high-caries adults, a bioactive composite might be considered in root caries or cervical lesions to prevent progression. Conversely, for a pristine Class I in a low-caries patient, a regular composite likely works just as well, and the bioactive aspect might not confer noticeable benefit – so the dentist might stick with what they know unless the new material offers a handling or speed advantage (like bulk fill in one go, etc.)

Additionally, guidelines should address technique. If a material is moisture-sensitive or requires a specific bonding approach, that must be highlighted. The anecdotal reports of Activa losing some restorations early could be mitigated if guidelines stress, for instance, the use of a quality bonding agent and perhaps avoiding heavy occlusal contacts for that material unless layered with a top surface of composite (one technique is a “sandwich”: Activa at the base for bioactivity, a conventional composite capping the surface for wear resistance). Guidelines might also consider combining strategies: say, using a bioactive liner/base in deep cavities under a conventional composite top. In fact, products like Activa can double as bases or liners (material scientists sometimes refer to them as “pulp-protective restoratives”). A hybrid approach could yield the best of both worlds – the robust wear surface of a composite and the ion release of a bioactive lining the cavity walls (Tiskaya et al., 2021, Tian et al., 2024).

5. Future Directions – New Pathways: The review would be incomplete without casting an eye to the future. “Recognizing new pathways” means identifying how we can further enhance restorative materials. One pathway is nanotechnology and optimized fillers – for example, nano-hydroxyapatite could be included to improve remineralization, or nanoparticles that have specific antimicrobial properties (like incorporating zinc or silver in small, safe quantities) could complement the ion release (Ástvaldsdóttir et al., 2015). Another pathway is smart polymers that respond to pH or enzymes by changing properties (imagine a matrix that expands slightly to release more agents when an acid attack is detected, then closes back). Research is also exploring bioactive composites that can actively trigger tissue regeneration, not just remineralization – for instance, materials that could stimulate odontoblasts or deliver growth factors to encourage secondary dentin formation under a deep restoration. These might one day allow a restoration to truly help heal the tooth from within.

For the immediate future, though, the simpler path is likely refining existing formulas – improving the strength of materials like Activa so that we don’t see any higher failure rates, perhaps by adjusting filler content or resin matrix to reduce water sorption (as water sorption can weaken resin over time but is a side effect of making it bioactive). We might also see more bulk-fill bioactives (Predicta is one; others will follow) so that efficiency in placement is coupled with bioactivity. Another concept being tried is coupling light-curing with bioactivity: some new resins cure in a way that leaves intentional nano-porosities for ion exchange, again balancing strength and ion release.

6. The Human Element: It’s worth mentioning in discussion that adoption of any new material involves a learning curve and acceptance by practitioners. Dentists naturally ask, “Is this material going to make my restorations last longer or be easier to use?” If the answer is yes, they will adopt it. Bioactive composites are gradually gaining interest; however, if a dentist has had stable success with traditional composites (which by now have a solid track record of 10–15-year lifespans in many cases), they might be hesitant to switch unless convinced of clear advantages. The mild redundancy in claims from various manufacturers (“releases fluoride!” – something many materials do, including older ones) might also lead to skepticism. Thus, part of the path forward is education and evidence dissemination. As more studies come out – especially independent clinical trials and long-term results – confidence in these materials will grow. We’re essentially in the early years of these products’ life cycle; they need to prove themselves. The good news is that so far none has proven a disaster (except that one concerning data set for Activa, which hopefully will be investigated and addressed). Most are doing quite well and as knowledge spreads, usage is likely to increase (Tiskaya et al., 2021).

In discussing limitations of our review: it is constrained by the same short follow-up of many studies we included. Also, not all bioactive materials on the market were covered in published studies – some data remain proprietary or anecdotal. There is also a publication bias to consider: if a new material had completely flopped in testing, it might not get published as readily. So, we must watch out for an overly positive slant. We attempted to mitigate that by including that negative Activa trial and by noting the risk of bias in many RCTs (very few were double-blind or had long-term follow-up; many had industry funding or authors with manufacturer affiliations as well). This doesn’t invalidate the results, but in discussion, one acknowledges that truly objective, long-term evidence is still forming.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Bioactive composite resins bring an innovative approach to restorative dentistry, aiming to combine the restoration of form and function with an active role in preventing future decay. Based on our comprehensive review of recent advances, we conclude that these materials have successfully demonstrated improved properties in vitro and promising performance in vivo. They reliably release fluoride and other ions, can neutralize acidic challenges in their environment, and exhibit mechanical strengths close to those of conventional composites. Clinically, their short-term performance (1–2 years) in both children and adults is comparable to traditional resin composites (Tian et al., 2024). In certain studies, they have shown superior outcomes in specific areas – for example, better marginal integrity or color stability for Activa in some trials, and giomer restorations have maintained exceptionally good quality even over a decade. These findings suggest that bioactive composites may prove to be viable option for immediate restorative dentistry, especially for patients who prove to be of increased caries re-infection risk and may stand to benefit from the preventative effects that these materials offer.

However, it is noticeably clear that future innovations and more detailed protocols are needed. The lack of extensive long-term clinical data and significant proof of the reduction of caries infections mean we don’t yet have a definitive answer that these materials significantly extend a compromised tooth’s longevity or reduce secondary caries incidence. The evidence so far suggests parity with conventional materials, but not a dramatic leap in outcomes (with the caveat that observation periods have been short). We also observed variability in results – not all bioactive materials perform identically, and some (like certain Activa applications) might underperform in high-stress restorations if not used judiciously. This underscores the need for refinement of material protocols and proper case selection.

In conclusion, bioactive composite resins offer a promising evolution of restorative materials and seem to present a promising future, aligning with the global emphasis toward minimally invasive and preventive dentistry. To fully utilize their potential, we recommend the following:

Expanded Long-Term Research: Encouragement of independent clinical trials with longer periods of follow-ups (5, 10 years) to truly assess the bioactive capabilities and lowered rates of secondary caries. Multi-center trials and registries tracking outcomes of bioactive restorations in practice would prove invaluable in order to more accurately assess whether or not the promise of these materials comes to fruition.

Standardize Evaluation Protocols: The adoption of common evaluation metrics (perhaps a blend of FDI and USPHS criteria for consistency) and clarification of the definition of “bioactive” in measurable terms will simplify the comparison of results across studies. This standardization could extend to laboratory tests of ion release in the different materials in question.

Material Improvements: Manufacturers should continue on their work to produce formulations to address weaknesses reported on these ¨experimental¨ materials. For example, improvements in the mechanical strength and polishment retention of Activa, or creation of more easily handled bulk fill resins, would make them more competitive with top-tier composites. Moreover, testing of other additives (like antibacterial nanoparticles) would most probably boost their role in being proactive materials. It’s recommended that companies be transparent in their data to help with the research that is being conducted to make the materials they make more attractive to our colleagues (Tiskaya et al., 2021).

Clinical Guidelines Development: International organizations, experts in the field, as well as global panels should produce guidelines and recommendations for bioactive restoratives. These guidelines would cover:

Indications

Placement Techniques

Finishing and Polishing

Patient Education

Preventive Oral Health Integration: The suggestion is to integrate bioactive composites into operative dentistry. For example, a high- risk patient could have a plan that has multiple different elements of minimally invasive procedures such as but not limited to fluoride varnishes, dietary counseling, and, where restorations are needed, the use of bioactive materials to reduce the likelihood of new lesions. In this way, the restorations align with and reinforce the preventive plan (Schwendicke et al., 2021).

In conclusion, the development of bioactive composites is a positive step toward a more holistic approach in dentistry. As these materials gain more traction and improve, we anticipate their role in clinical practice to grow thus helping and improving future research in the field. With proper guidelines, bioactive composites can be incorporated effectively into every day clinical use – helping to achieve restorations that not only repair damage but contribute to the long-term health of the tooth as well. This is an interesting trajectory, one that aligns with the mission of preventive dentistry and the vision of caries management moving forward, shifting from the common dental care which is more reactive rather than proactive. The coming years will be crucial in validation and refinement of these materials and techniques, aiming to give patients restorations that last longer and teeth that stay healthier. The path has been laid; now it is up to continued research to fully bring these materials into the mainstream and prove if they are indeed the next step of restorative dentistry, really bringing the whole philosophy of minimal invasion, proactive care and long-term restorative solutions into play (Gordan et al., 2015).

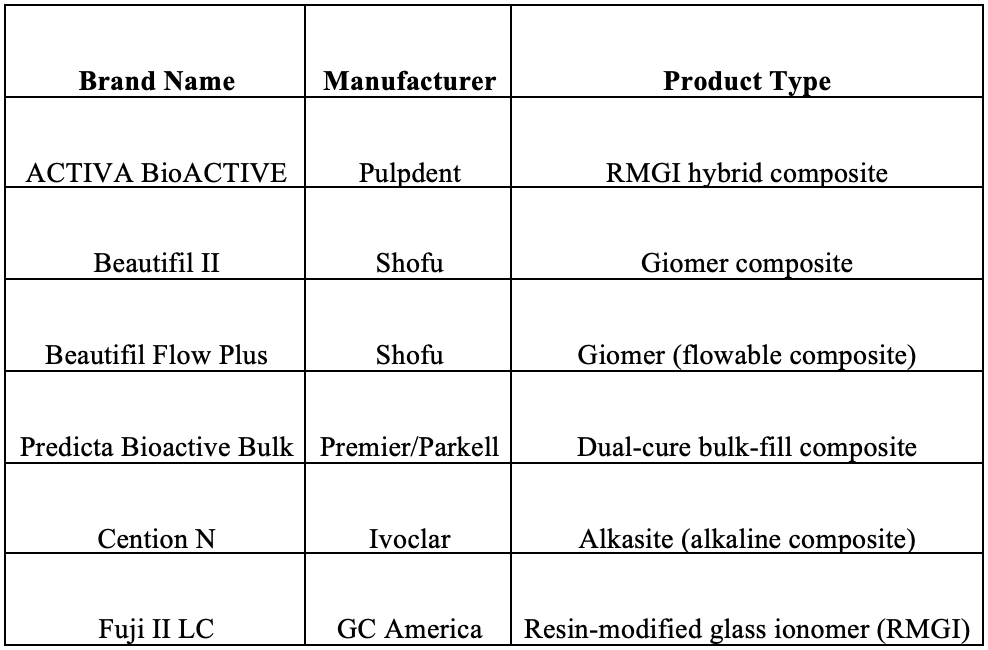

Appendix – Bioactive Restorative Products (Brands, Manufacturers, and Types)

The table below lists the bioactive restorative materials mentioned in the document, along with their manufacturers and product categories:

References

1. Albelasy, E. H., Hamama, H. H., Chew, H. P., Montaser, M., & Mahmoud, S. H. (2022). Secondary caries and marginal adaptation of ion-releasing versus resin composite restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Scientific Reports, 12, Article 19244. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19622-6

2. Ahmed, B., Syed Zubairuddin, S., & Muddassir, M. (2024). Enhancement of flexural and shear bond strength of Class II bioactive composite restorations with different cavity designs and adhesion techniques. Scientific Reports, 14, 17482. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64765-w

3. Ástvaldsdóttir, Á., Dagerhamn, J., van Dijken, J. W. V., Naimi-Akbar, A., Sandborgh-Englund, G., Tranæus, S., & Nilsson, M. (2015). Longevity of posterior resin composite restorations in adults, A systematic review. Journal of Dentistry, 43(8), 934–954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2015.05.001

4. Banerjee, A., Frencken, J. E., Schwendicke, F., & Innes, N. P. T. (2017). Contemporary operative caries management: Consensus recommendations on minimally invasive caries removal. British Dental Journal, 223(3), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.672

6. da Rosa Rodolpho, P. A., Collares, K., Corrêa, M. B., Demarco, F. F., Opdam, N. J. M., & Moraes, R. R. (2022). Clinical performance of posterior resin composite restorations after up to 33 years. Dental Materials, 38(4), 680–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2022.02.009

7. de Carvalho, L. F., Silva, M. G. E., Barboza, A. S., Badaró, M. M., Stolf, S. C., Cuevas-Suárez, C. E., Lund, R. G., & Ribeiro de Andrade, J. S. (2025). Effectiveness of bioactive resin materials in preventing secondary caries and retention loss in direct posterior restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Dentistry, 152, Article 105460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2024.105460

8. Ferracane, J. L., Sidhu, S. K., Melo, M. A. S., Yeo, I. S. L., Diogenes, A., & Darvell, B. W. (2023). Bioactive dental materials: Developing, promising, confusing. JADA Foundational Science, 2, Article 100022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfscie.2023.100022

9. Gordan, V. V., Blaser, P. K., Watson, R. E., Mjör, I. A., McEdward, D. L., Sensi, L. G., & Riley, J. L. (2014). A clinical evaluation of a giomer restorative system containing surface pre-reacted glass-ionomer filler: Results from a 13-year recall. Journal of the American Dental Association, 145(10), 1036–1043. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.2014.57

10. Gordan, V. V., Mondragon, E., Watson, R. E., Garvan, C., & Mjör, I. A. (2007). A clinical evaluation of a self-etching primer and a giomer restorative material: Results at eight years. Journal of the American Dental Association, 138(5), 621–627. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0233

11. Heintze, S. D., Loguercio, A. D., Hanzen, T. A., Reis, A., & Rousson, V. (2022). Clinical efficacy of resin-based direct posterior restorations and glass-ionomer restorations—An updated meta-analysis of clinical outcome parameters. Dental Materials, 38, e109–e135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2021.10.018

12. Heintze, S. D., & Rousson, V. (2012). Clinical effectiveness of direct Class II restorations, A meta-analysis. Journal of Adhesive Dentistry, 14(5), 407–431.

https://doi.org/10.3290/j.jad.a28390

13. Hofsteenge, J. W., Scholtanus, J. D., Özcan, M., Nolte, I. M., Cune, M. S., & Gresnigt, M. M. M. (2023). Clinical longevity of extensive direct resin composite restorations after amalgam replacement with a mean follow-up of 15 years. Journal of Dentistry, 130, Article 104409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2023.104409

14. Imazato, S., Nakatsuka, T., Kitagawa, H., Sasaki, J.-I., Yamaguchi, S., Ito, S., Takeuchi, H., Nomura, R., & Nakano, K. (2023). Multiple-Ion Releasing Bioactive Surface Pre-Reacted Glass-Ionomer (S-PRG) Filler: Innovative Technology for Dental Treatment and Care. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 14(4), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb14040236

15. Kametani, M., Akitomo, T., Hamada, M., Usuda, M., Kaneki, A., Ogawa, M., Ikeda, S., Ito, Y., Hamaguchi, S., Kusaka, S., Asao, Y., Iwamoto, Y., Mitsuhata, C., Suehiro, Y., Okawa, R., Nakano, K., & Nomura, R. (2024). Inhibitory Effects of Surface Pre-Reacted Glass Ionomer Filler Eluate on Streptococcus mutans in the Presence of Sucrose. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(17), 9541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25179541

16. Kasraei, S., Haghi, S., Valizadeh, S., Panahandeh, N., & Nejadkarimi, S. (2021). Phosphate Ion Release and Alkalizing Potential of Three Bioactive Dental Materials in Comparison with Composite Resin. International Journal of Dentistry, 2021, Article 5572569. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5572569

17. Kopperud, S. E., Tveit, A. B., Gaarden, T., Sandvik, L., & Espelid, I. (2012). Longevity of posterior dental restorations and reasons for failure. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 120(6), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/eos.12004

18. Marović, D., Par, M., Posavec, K., Marić, I., Štajdohar, D., Muradbegović, A., Tauböck, T. T., Attin, T., & Tarle, Z. (2022). Long-Term Assessment of Contemporary Ion-Releasing Restorative Dental Materials. Materials, 15(12), Article 4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15124042

19. Miki, S., Kitagawa, H., Kitagawa, R., Kiba, W., Hayashi, M., & Imazato, S. (2016). Antibacterial activity of resin composites containing surface pre-reacted glass-ionomer (S-PRG) filler. Dental Materials, 32(9), 1095–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2016.06.018

20. Neto, C. C. L., das Neves, A. M., Arantes, D. C., Sa, T. C. M., Yamauti, M., de Magalhães, C. S., Abreu, L. G., & Moreira, A. N. (2022). Evaluation of the clinical performance of GIOMERs and comparison with other conventional restorative materials in permanent teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-Based Dentistry. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-022-0281-8

21. Nomura, R., Nakano, K., Matayoshi, S., Kitamura, T., & Okawa, R. (2021). Inhibitory effect of a gel paste containing surface pre-reacted glass-ionomer (S-PRG) filler on the cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Scientific Reports, 11, Article 18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80646-x

22. Opdam, N. J. M., van de Sande, F. H., Bronkhorst, E. M., Cenci, M. S., Wilson, N. H. F., & Demarco, F. F. (2014). Longevity of posterior composite restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Dental Research, 93(10), 943–949. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514544217

23. Oz, F. D., Meral, E., & Gurgan, S. (2023). Clinical performance of an alkasite-based bioactive restorative in Class II cavities: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Applied Oral Science, 31, e20230025. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7757-2023-0025

24. Özer, F., Patel, R., Yip, J., Yakymiv, O., Saleh, N., & Blatz, M. B. (2022). Five-year clinical performance of two fluoride-releasing giomer resin materials in occlusal restorations. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry, 34(8), 1213–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12948

25. Özer, F., Unlu, N., Sengul, F., & Blatz, M. B. (2021). Three-year clinical performance of two giomer restorative materials. Operative Dentistry, 46(1), E60–E67.https://doi.org/10.2341/17-353-C

26. Pinto, N. S., Jorge, G. R., Vasconcelos, J., Probst, L. F., De-Carli, A. D., & Freire, A. (2023). Clinical efficacy of bioactive restorative materials in controlling secondary caries: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health, 23(1), Article 394. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03110-y

27. Pires, P. M., Neves, A. A., Makeeva, I. M., Schwendicke, F., Faus-Matoses, V., Yoshihara, K., Banerjee, A., & Sauro, S. (2020). Contemporary restorative ion-releasing materials: Current status, interfacial properties and operative approaches. British Dental Journal, 229(7), 450–458. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2169-3

28. Pires, P. M., Rosa, T. d. C., Ribeiro-Lages, M. B., Duarte, M. L., Cople Maia, L., Neves, A. d. A., & Sauro, S. (2023). Bioactive Restorative Materials Applied over Coronal Dentine—A Bibliometric and Critical Review. Bioengineering, 10(6), 731. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10060731

29. Slimani, A., Sauro, S., Gatón Hernández, P., Gurgan, S., Turkun, L. S., Miletic, I., Banerjee, A., & Tassery, H. (2021). Commercially Available Ion-Releasing Dental Materials and Cavitated Carious Lesions: Clinical Treatment Options. Materials, 14(21), 6272. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14216272

30. Spagnuolo, G. (2022). Bioactive dental materials: The current status. Materials (Basel), 15(6), 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15062016

31. Toz-Akalin, T., Öztürk-Bozkurt, F., Kusdemir, M., Özsoy, A., Yüzbaşıoğlu, E., & Özcan, M. (2024). Three-year clinical performance of direct restorations using low-shrinkage Giomer vs. nano-hybrid resin composite. Frontiers in Dental Medicine, 5, Article 1459473. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdmed.2024.1459473

32. Van Dijken, J. W. V., & Pallesen, U. (2013). Four- to 12-year evaluation of posterior resin composite, glass ionomer, and resin-modified glass ionomer restorations. Dental Materials, 29(2), 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2012.10.015

33. Vetromilla, B. M., Collares, K., Opdam, N. J. M., Kramer, G., Moraes, R. R., & Demarco, F. F. (2020). Longevity of posterior resin composites: A network meta-

analysis. Journal of the American Dental Association, 151(6), 386–395.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2020.01.003

35. World Health Organization. (2022). Global oral health status report: Towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. World Health Organization.

36. Zhang, O. L., Niu, J. Y., Yin, I. X., Yu, O. Y., Mei, M. L., & Chu, C. H. (2023). Bioactive materials for caries management: A literature review. Dentistry Journal, 11(3), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11030059